Back to Chapter Headings Back to home page Contact Gene Lantz

By 1970, I had been a practicing liberal for 5 years. I was never comfortable with my new outlook, but the pace of change was such a whirlwind that it was all I could do to keep up. I had gone from a know-nothing do-nothing backward country boy to an urban, college-educated, intensely interested person. But still, I didn't know beans.

As I didn't know much of anything and was painfully aware of it, I tended to put a lot of stock in the ideas of others. I think I particularly admired some of my new friends who were teachers at Rice University. I went to church with them at First Unitarian in Houston. I was on the Involvement Committee. I really liked my new circle of urban liberals. I looked up to them.

One family, I thought, was especially progressive. It was with them that I first began to think that my ideas about education could actually take existence. Just about all liberals in those days had read the popular book "Summerhill," about an English boarding school. "Freedom cures most things," was my favorite quote from author/headmaster A.S. Neill. All the liberals loved A.S. Neill. Another of the urbane friends was an actor, Noble Willingham. Noble became famous later on as the old Texas Ranger who advised Chuck Norris in his long-running TV show. At this time, he was a salesman for a freight company, where I worked on the loading dock. But Noble dabbled in theater and told great stories to his friends in the Montrose district of Houston.

For an uncultured country boy, this was a world where dreams seemed to come true, at least in conversations. I committed to my dream, what I had been calling a "someday school" where corporal punishment, and any form of aversive control, would not be used on children. Reality was just circling around outside my view, but it was about to swoop in like an army helicopter in Vietnam.

In late July, 1970, the swooping was swooped.

After I had committed my entire career and everything I owned to starting my dream school, Lille Skole, I had to have 3 board members. None of my liberal friends would accept a spot on the board. It wasn't much of a commitment, in fact it wasn't a commitment at all, since there was no financial risk, but they just wouldn't do it. Then the main parents who had dreamed up the school with me backed out. Their kids weren't going to go to the school. I had corporate papers with nobody to sign them, I had rented a school building with no children to teach!

Then something, seemingly unrelated, happened in Houston's 5th ward.

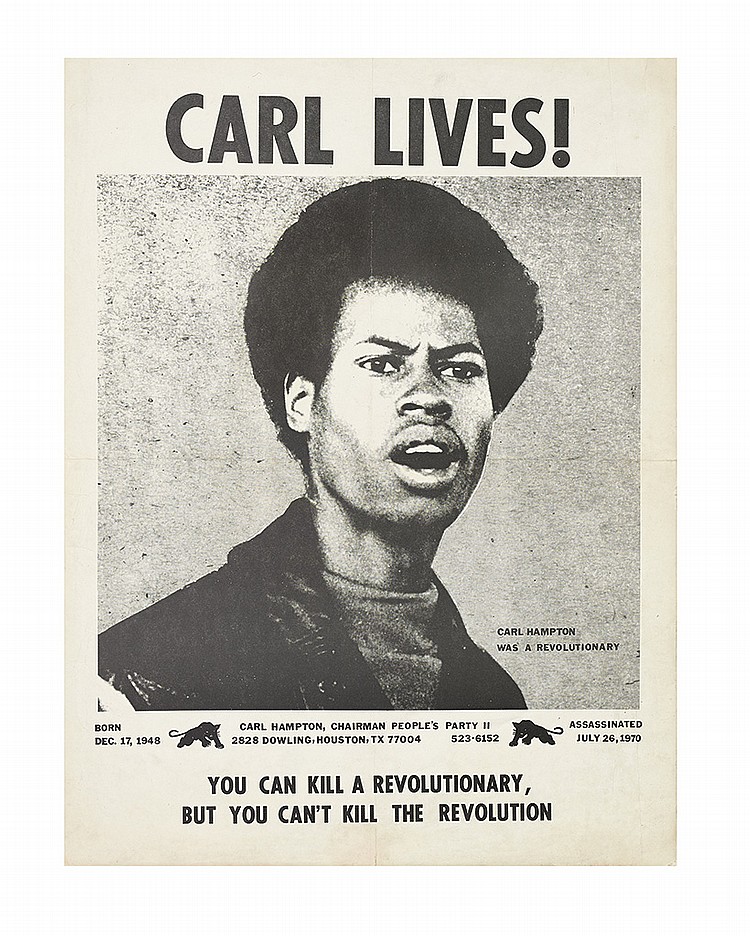

Some of the kids who sold newspapers reflecting the views of the Black Panthers were told, by Houston police, that they couldn't sell newspapers. It's a constitutional right, but the Houston police didn't want it extended to these African American children. A showdown ensued. If you know any history, you know that the Panthers took the second amendment literally and insisted on their right to carry guns. Fred Hampton and his Panthers had already been massacred by the Chicago police earlier that summer, so things were tense. Fred's cousin, Carl Hampton, had tried to start a Black Panther chapter in Houston, but the Panthers wouldn't let him, so Carl and his group called themselves "People's Party II." But they still insisted on the right to carry weapons.

When the police tried to arrest the newpaper vendors, Carl pulled his weapon. The police had to back down, probably not so much because of the weapon but maybe because they knew that they were outside the law in denying anybody the right to sell newpapers. But the hint of violence was enough to make the papers, and the situation was sure to escalate.

I remember Noble commenting on the whole thing. I was stunned by his cynicism. He said that Carl Hampton committed suicide, because anybody who pulled a gun on a Houston policeman was marking himself to die. And sure enough, the Houston police set snipers on the rooftoops that Sunday night around the People's Party II headquarters and shot Carl Hampton dead. They bragged about it on the police radio and KPFT, the Pacifica radio station, aired it. Everybody in Houston heard them: "I got one, I think it was the leader!".

The assassination of Carl Hampton was only a curious incident to my liberal friends, and Noble actually thought it was a natural development. What was really bothering me was that I had just put my entire career on the lline over this school idea and then lost all my liberal supporters. But it came together when I set out for class that Wednesday. On the way, I dropped in on a young liberal female friend of whom I was particularly fond. Her own favorite friend in those days was Mickey Leland, a pharmacy student who was working with People's Party II to build a "People's Pharmacy" to serve poor people in the African American Community. Mickey, yes, the one who later became a popular U.S. Congressman, was rounded up and jailed with supporters of the Panthers, so my friend was upset about it and passed those feelings along to me. She was afraid that Mickey would be killed while he was in jail, or that he might be charged with something and never get out of jail. It was upsetting.

When I sat down in the classroom, I opened the school paper. The University of Houston newspaper headline was "Houston Police Murder Carl Hampton!" Reality had finally hit me in the face. Almost immediately, I sought out the only African American in the class and sought sympathy. He was basically unaffected by the assassination, but he started giving me an abstract talk about civil rights that, I soon realized, was really just a talk about himself. It was just talk. He didn't even know who Carl Hampton was. I overheard a white classmate commenting, "It's just some bad apples, it's not the system." I couldn't resist getting into an argument with him because it was painfully obvious, since the police were acting under official orders, that they weren't bad apples. It really was the system.

We grew quiet as the lecture started. That is, everybody else grew quiet. Me, I started bawling. Remember that I'm talking abut graduate school here, not elementary or high school, so it must have seemed unusual for a class full of longtime educators, school principals, and even a few superintendents, to see somebody fall out of his seat crying. But I did.

The professor ushered me outside. This is where I remind you, reader, that I'm not just recounting my life here. I'm trying to explain how I learned life's lessons and what those lessons were.

I thought he'd just get me out of the classroom, since I was distracting, but the professor stayed with me in the hallway. He listened sympathetically while I blubbered that the Houston police, my police, the ones my taxes paid for, had murdered Carl Hampton. By way of trying to excuse my breakdown, I also told him that I was going through a hard time because I had put my career on the line because I had believed my friends who had said they would back me, and then they had just pulled the carpet right out from under.

This is the lesson part:

The old professor was about half my size, but he hugged me as well as he could. Then he told me, "You have learned a valuable lesson."

"What?" I blubbered.

"Never trust a liberal!"

Back to Chapter Headings Back to home page Contact Gene Lantz